In my early twenties, I stayed up late one evening with a coworker who was also a close friend, at his parents', after a day of fishing. We both worked at a residential program, primarily with heroin addicts, and it had been a long week. He was a vet and had previously told me of events during his two terms in Viet Nam--how he had lied and enlisted underage and then reenlisted after his first tour was over, because he was unable to deal with his return to civilian life. He shared how, in Viet Nam, he would sneak away and go to a local brothel, not for the girls, but because the woman in charge reminded him of his mother and treated him like a son. He still knew the words and phrases she had taught him and he had me learn them, too. He had no medals. He told me he had often won commendation, but would just as quickly turn around and do things that would earn him demotion. I was hardworking, and so was he, so I was puzzled that he would have regularly forfeited his "prizes." I had not yet connected prizes and "accomplishments" in a war zone.

Perhaps because it had been a very long day, or perhaps because all of the prior stories had set the stage, that night he began to share his experiences as a helicopter door gunner. I was young and I was naive and, before I knew it, his eyes were wide and his breathing quick and there was the feeling that we were in the door of the helicopter, side by side. The women gathered below, like his mother away from home, and their children, were numerous and close--he could see each

one's face, looking up at him--as he did the job that was expected of him, drilled into him, as an American

helicopter door gunner, in Viet Nam. He could barely articulate what he had just done and he was incoherent about what he was seeing, but the movement of his eyes, his posture and his imaginary weapon told the story, as did the shock and bewilderment in his eyes.

Later, he gave me his camos. I still have his jacket. Even years later, after we lost contact but happened to run into each other in another city on a couple of occasions, he refused to take it back, insisting I was the best person for it. I am just a little bit taller than petite, but it is too small for me, maybe a boy's size 16, not much larger. After a dozen moves and a million things lost, I still have it.

I hear my friend, again, as I listen to this soldier narrate this video we were never meant to see--he was there that day in Iraq, in the aftermath. We haven't learned much, because we don't admit where we've been or what we've done. We offshore the pain and suffering of our wars and try "not to look." It's not healthy. We owe it to them to sit alongside, and look.

Al Jazeera Witness 23 Aug 2012 10:56

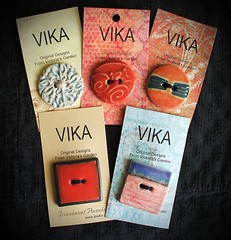

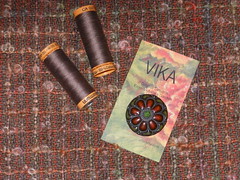

After she'd received the button, I received a link to a picture of the button, along with the handwoven fabric. She also informed me that her plan was to enter the finished suit in this year's Make It With Wool competition. I had imagined the button as jewelry or as a button on a suit, but it had never occurred to me it might become something more.

After she'd received the button, I received a link to a picture of the button, along with the handwoven fabric. She also informed me that her plan was to enter the finished suit in this year's Make It With Wool competition. I had imagined the button as jewelry or as a button on a suit, but it had never occurred to me it might become something more.